In 1999 he graduated in architecture from IUAV with a thesis on the discovery of concrete and its use as an innovative material in architecture. Martina Chiarato He founded the Archetipo studio together with Michela Stevanato. Today Archetipo Associated ArchitectsBased in Marcon (Venice), the company has extensive experience in the field of architectural design, interior design and restoration of building complexes. Among the achievements, the projects for the installation and restoration of the Carive collection at the Querini Stampalia Foundation and at Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin stand out. Architect Chiarato understands from the earliest studies like this “is the result of a wonderful puzzle in which each architectural and technical element plays an essential role in the whole“.

Interview with the architect Martina Chiarato

To compete with the Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin, it was imperative that you confront its complex design history and rebuild it from the ground up. What was it like picking up the original records again?

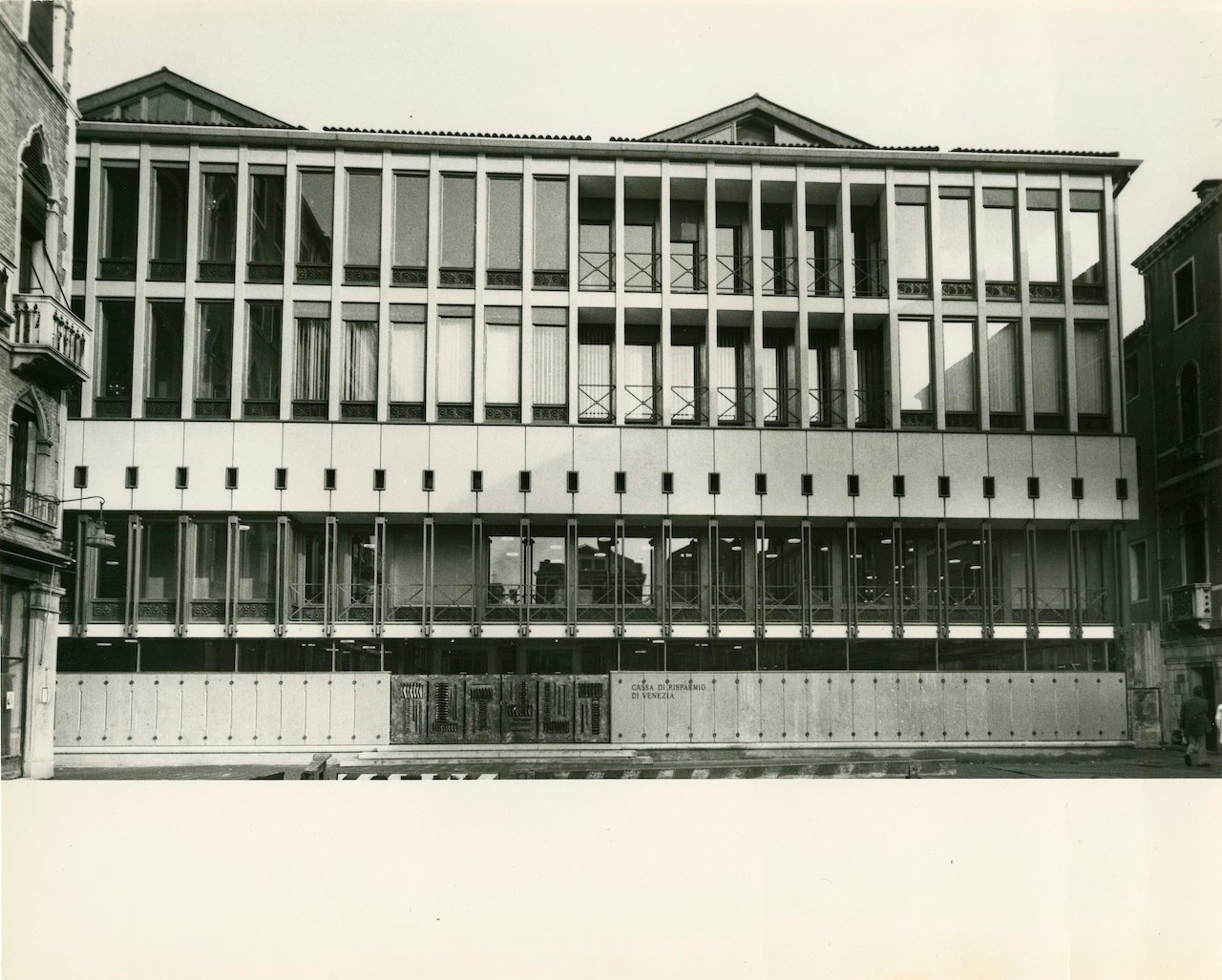

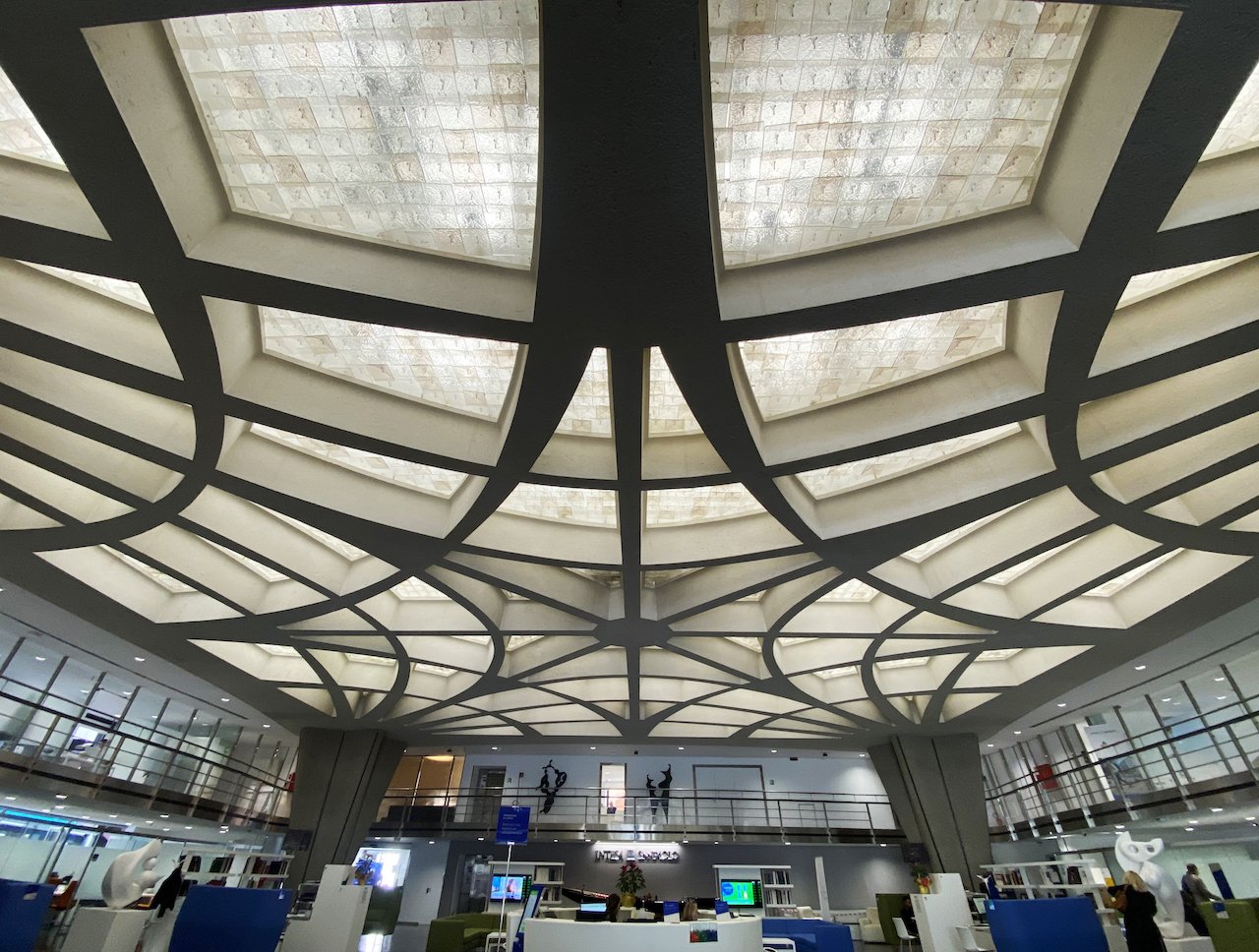

The preparatory study for the philosophical approach to the restoration of the Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin was a valuable technical and architectural lesson for me. Nervi’s masterful works, despite the simplicity of the end result, are a condensation of what he called the “science or art” of building: a magnificent partnership between engineering and architecture in which neither discipline ever prevails over the other. Rather, there is a mutual exchange between the contributions of one and the other whose end result is the only possible one, for the place where the work is carried out and for the function to which it must respond. For this reason, a project is never the same and the Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin is also a unique work in which the constants, that is the use of reinforced concrete, the attic with isostatic ribs, the metal frames and the spiral staircases, adapt to the depending Place and function always have an original, timeless connotation.

How did you work?

The myriad of graphic tables, starting with the definition of the provisional works, ending with the study of the details of the steel mullion of the parapet of the staircase, made me realize that in this work, more than in any other, the restoration approach was necessarily necessary to begin with the attempt to restore the to bring to light a detailed design process in which every smallest component, when understood, reveals its dual nature: functional and aesthetic. The removal or modification of even one of these elements would only have exposed the deficiency, but it is true that buildings must continue to live and fulfill their social function, responding to the renewed needs of society itself. The result of my intervention is therefore a compromise between innovation and conservation, the former, always recognizable, being subordinate to the latter.

What condition was the building in before the work? How did you intervene?

The building, which was in excellent condition for which the restoration work was very limited, nevertheless had to be adapted to the changed functional needs. Again, from a compositional point of view, there was no need to overturn it: some tricks were required for it to be fully responsive to the client’s wishes; This, too, is one of the aspects that contribute to Pier Luigi Nervi’s work being disarmingly contemporary.

What was the biggest challenge for you during the restoration?

The aim was to search for the cause of a suspected lowering of the mezzanine floor, which revealed an obvious injury in the connection between the top floor and the facade with metal strip windows. We started by examining the way the mezzanine supports itself – a way that isn’t so explicit at first glance – in order to be able to understand how some elements that are only seemingly decorative, like the Theory of the steel mullions dividing the mezzanine The rhythm of the definition of the glazed offices as well as the external offices that adorn and embellish the facade actually fulfill the main static function.

And then?

It is only when passing through the technical room, just over 2 meters high, necessary for the distribution of the systems, that the heads of the uprights appear, because they are elegantly covered by an original copper cladding, which also performs the function of protecting the support rods of the mezzanine. The result was that the mezzanine was in optimal static condition and there was no need to find any support other than that originally planned or implemented, and the settlement was nothing more than the result of a different reaction to the loads on the part of the building mezzanine (made of steel and wood, therefore flexible) and the curb between the two floors (made of reinforced concrete, therefore very rigid).

The building bears the signature of Pier Luigi Nervi for the structures, Angelo Scattolin for the architecture and prominent artists for the decorations; including the sculptor Simon Benetton, author of the Bronze Gate. It also features a double facade that allows for a very different dialogue with two different squares. What fascinates you most about the synthesis of expressive forms and the urban role of the building in the historical structure?

As already mentioned, the Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin, despite being a modern work, does not enter the Venetian environment with a straight leg, but integrates perfectly with its fragile structure through a multitude of elements: Respect for the rhythm of bodies and voids, the preference for the verticality of the windows and the proposal of traditional elements, albeit reinterpreted in a modern way, like the glass mosaics by Murano that draw the horizontal line of the floors as well as that of the wrought iron. I believe that the great success of this work also lies in showing that architecture must never be an end in itself, but must be conceived by the geniuses of the place where it stands, that it must carry its legacy. Only in this way do the places where we live belong to us and we are not afraid to cross them instead of going around them, as is the case with this building when the Venetians enter to move from part of the city to the Go through the Campo San Luca entrance and cross the hall to exit the Campo Manin entrance and continue to the destination from here.Maria Chiara Virgili

DISCOVER HERE the restoration project

BUY the book on Palazzo Nervi-Scattolin HERE

Bibliographic Sources

Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia (edited by), The new headquartersModern graphics, Verona 1975

A. De Magistris, F. Deambrosis, Nervi Scattolin Palace. VeniceSkira, Milan 2020