The oldest photography festival in Italy takes place in Savignano sul Rubicone in Romagna. This year, SI FEST, which is under the artistic direction of photojournalist Alex Majoli for the second time, is entirely dedicated to the project eyewitness (the exhibitions are still open to visitors on the weekends of September 16th and 17th and 23rd and 24th). The protagonists include Marco Zanella (Parma, 1984), who won the Pontrelli Prize in 2021 with the book Scalandré (Cesura Publish). Arianna Arcara, Cristina De Middel and Lorenzo Vitturi are now exhibiting with him in the building of the former Savignano Land Reclamation Consortium: Everyone haslooked around” to so many Prisoners of the prison of Forlì. We also spoke about this with Zanella, member of the Cesura collective and also present in the OFF section of the festival, with some large format photos taken in Romagna during the days of the flood (the images are included in the fanzine). embankmentspublished with the aim of collecting donations for the areas affected by the disaster).

Interview with photographer Marco Zanella

How your two works came about “for Vitaliy” And “for Rahma” as part of the Eyewitness Project?

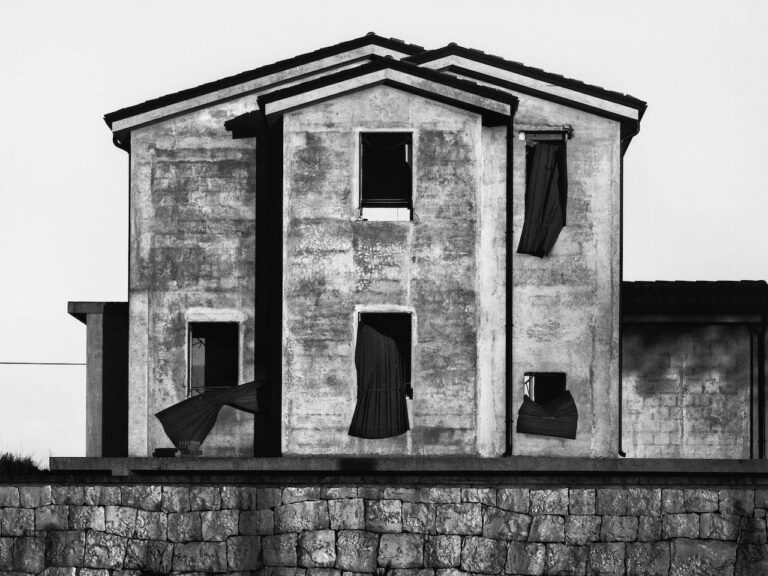

Alex Majoli called us for this assignment that he had had in mind for many years, at least since I knew him in 2011-2012. The idea was to work with people incarcerated in a prison to become their gaze. People who, for one reason or another, by chance, by the law of chaos, because they have chosen a path on the left instead of the right, are restricted by an architectural barrier where there is a wall, borders, lines Floor, keys and doors that separate you from the outside world.

Was this your first time in a correctional facility?

Yes, the Forlì prison is located in the ancient Rocca di Ravaldino. I knocked and

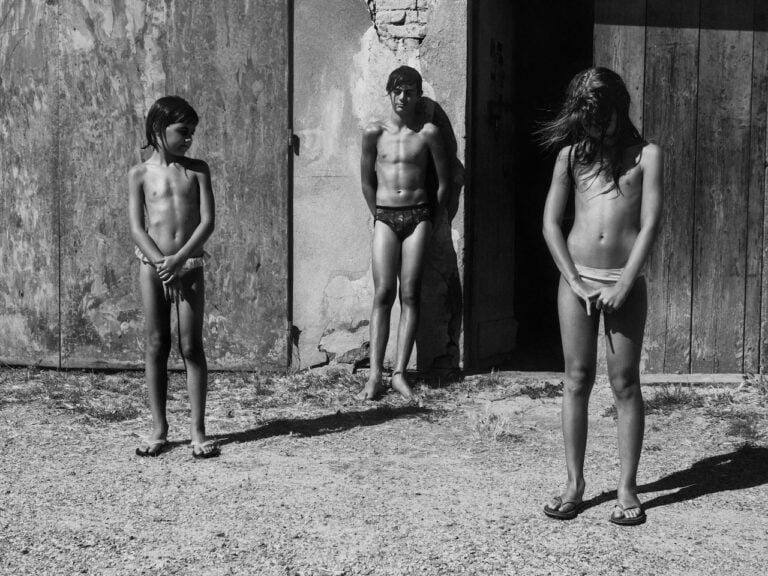

I entered. One door, two doors, controls, three doors, four doors… Then I came to the area where prisoners usually interview lawyers, but which became the “photographer’s room” for a day or two. I believe there was a selection process within the prison to determine which of the inmates was most suitable and available to work with us photographers and organize the festival. Personally, I have worked with two prisoners and two different stories, in southern Italy and Morocco.

What connection did you have between the meeting and the photography?

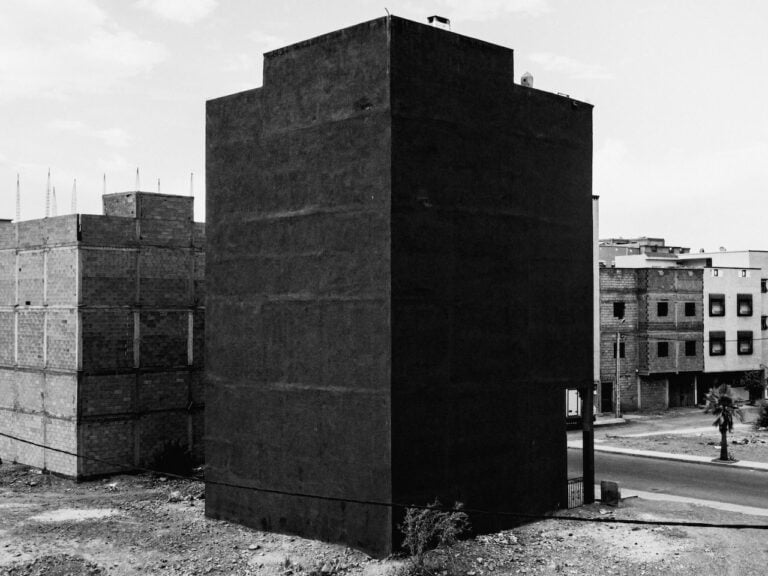

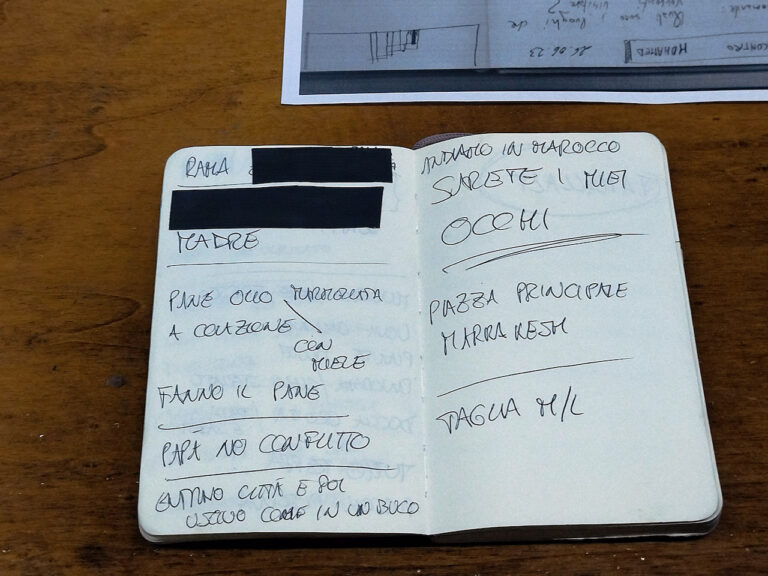

I just talked to them about the project. I asked them what they would like to see outside of prison based on the photos: an hour or two of conversation, jotting down sentences and notes in my Moleskine notebook. I worked for Vitaliy, a prisoner from San Vitaliano (Naples), and Rahma, a girl originally from Morocco. At first she was unsure, she told me that she would like to see the cities at night and photograph the sunsets. As we talked, it turned out that part of his family lives in Italy and the other in their country of origin. His father returned to Morocco: I suggested meeting him and together we agreed that I would surprise him. I left for Morocco on August 15th and spent seven days retracing the journey she took as a child and returned on vacation in the summer. I stayed with part of the girl’s family for four days, I went on trips to the countryside with her father, we went into the mountains among the Berbers, together we saw a horse fantasy. It was wonderful.

1/10

1/10 2/10

2/10 3/10

3/10 4/10

4/10 5/10

5/10 6/10

6/10 7/10

7/10 8/10

8/10 9/10

9/10 10/10

10/10Watch out for the prisoners. The Eyewitness Project

So, like Vitaliy, whose friends and parents you met in San Vitaliano, was it about describing an encounter?

I don’t just tell stories, I photograph everything that interests me. I’m a pretty compulsive photographer who takes photos a lot, so I capture a lot of the reality of my things. As if it were a pair of scissors, I cut out endless fragments, puzzle pieces that I take from the reality of my journey, and then bring them all home. This is where the narrative emerges about what is told and what is not.

Have the inmates seen these photos?

Not yet. We are organizing the second part of the project, which consists of returning to the prison to show them the photos that were not selected.

“Let’s go to Morocco / You will be my eyes,” they wrote on the diary page displayed in the display case. What is the relationship between photography and writing for you?

Not that I’m good at writing, writing is a way to clear my head. Most of the time I don’t re-read what I write. When I arrive at a place, I write something down so I don’t have too many thoughts and can take photos. In fact, as in San Vitaliano and Morocco, when I arrive in a place that I don’t know, I am so stimulated by what I see that I have to free myself from the fear of having to photograph everything I note do: the things I want to do I like to take photos, the calendar of days. This gives me the freedom to take photos. One of the biggest mistakes for me is actually thinking when taking photos.

So does the writing precede the shooting?

It not only precedes it, but accompanies it. I have a collection of about thirty or maybe forty Moleskines between the ones I use in the studio and others I keep with me that contain pieces of my life. Writing is helpful. The more I write, the more relieved I feel looking, walking, and taking photos in every direction.

Photography after Marco Zanella

To what extent are you a “pretty compulsive-obsessive photographer”?

Since I started studying this language in 2005, all I have done is take photographs. Photography is a performative act. In the sense that I really like taking photos of everything.

For you, photography also means tidying up?

No, I just think it’s therapy to not feel too non-conformist. At least that’s what it was for

myself. Before, I was a very insecure person. Photography helped me a lot when I was depressed, to get to know the world inside me. Photography has become the most important way to enjoy the world.

When did you come into contact with photography?

When my uncle Giorgio, my father’s brother, died, I got his two cameras, one analog and one digital. So between 2004 and 2005 I started photographing my friends. Then I met the artist Matteo Ferretti, who was one of my closest friends and perhaps my first teacher. When I left Parma I went to Cesura, where I met Alex Majoli: by visiting the collective I unlearned everything I had learned and started all over again.

Which instrument do you play?

I was never a great musician, but I’ve always had a passion for electric guitar, rock music, metal and blues. Music and photography are the same thing for me. The idea is always to take fragments. In music, they are fragments that you sometimes create accidentally, change, experiment with electronics, and then there is someone who helps you put them together. In photography it’s the same, it’s about putting these fragments together.

How important is distance in your vision as a photographer?

Editing photos is a delicate matter, a very interesting process that involves looking at yourself from the outside and checking what you see. Sometimes it becomes a process of personal catharsis. There is infinite poetry in distance.

Manuela De Leonardis