One of them, Gianni, is a music philologist and translator (he edited Kierkegaard’s aesthetic works for the BUR “Classics of Thought”), playwright at the Teatro Stabile in Catania and teacher of dramaturgy at the Accademia di Mimodrama in Naples; the other, Giuseppe, is a musicologist and art historian. Both are passionate collectors. And we talked to the Garrera brothers about collecting in its various forms on the occasion of the exhibition Life is something differentwhich brought a core of the Garrera collection, linked to an idea of art as poetic struggle, to the La Rocca Foundation in Pescara.

Interview with Gianni and Giuseppe Garrera

How did your collecting adventure begin?

With the arrival in Rome, from the first foray through the city, in the forced encounter with the ancient ruins and later with the shocking, less obvious discovery of the ruins that also creates and spreads modernity. The first assets to be owned were the etchings of Piranesis, born from a bankruptcy of assets: in a moment the art, the charm of the ruins, the dispersion of inheritances, the economic adventure (the figure of a work of art is always in the fantastic order). because it goes beyond ordinary expenditure criteria), the absolute superfluity and noblesse of the object: all this has produced the sign of recognition of the conquest of a country through plunder, in any case an imperialist method. In Rome, you don’t need much time to stroll through galleries, antique dealers, second-hand dealers and ateliers and dream of embellishing everyday life with things, objects and materials, knowing that sooner or later you will come across something enchanted object .

What path has your collecting taken over time?

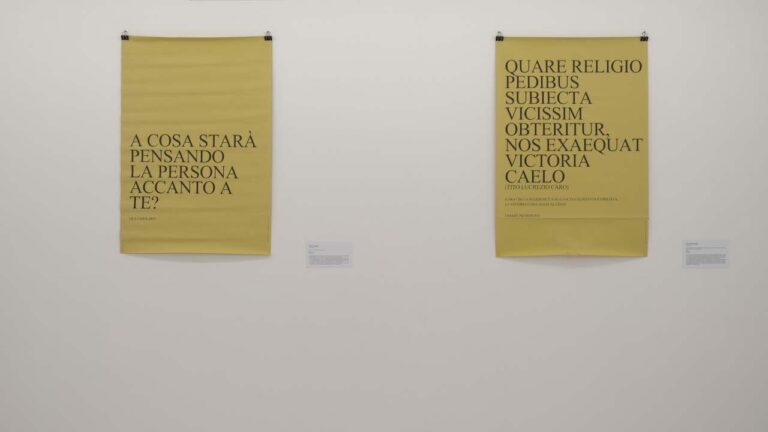

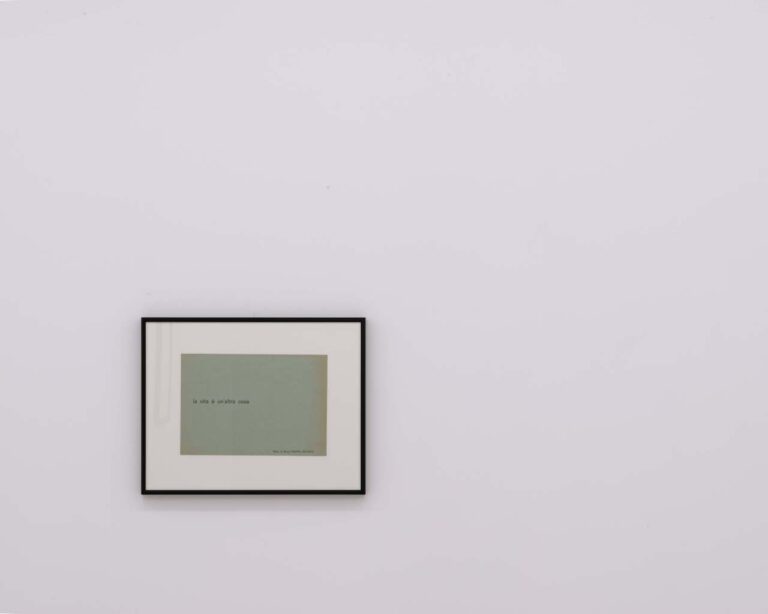

It originally arose from a vice of youth: books and reading (that is, many days unjustifiably spent reading in the middle of life); The childish desire to accumulate and own a large library was soon corrupted by contact with the rare bindings, the first valuable and special books and the artist’s books purchased, to the point of hunting for materials and idols (in the beginning still papers) and colors , gold, enamel and blue (we would say more and more blue and gold). It was precisely a change in attitude that sanctioned an aesthetic development: from the book that was held in the hand and eagerly read during the years of adolescence and youth to the book laid out like an exhibition. It seemed immediately clear to us that the work of art which used the word itself and which we had come to know was an appendage of the art of eloquence. We were faced with a series of works that we began to collect because they had in common the presentation of the word, the grammatical appearance, the unity of the logical and illustrative beauty of sentences, judgments and definitions. We were interested in the typographical aspect of persuasion, the mental phenomena that become visible signs, the artificial writing of concrete poetry. It was a transfiguration of our youth library.

1/11

1/11 2/11

2/11 3/11

3/11 4/11

4/11 5/11

5/11 6/11

6/11 7/11

7/11 8/11

8/11 9/11

9/11 10/11

10/11 11/11

11/11The Garrera brothers’ art collection

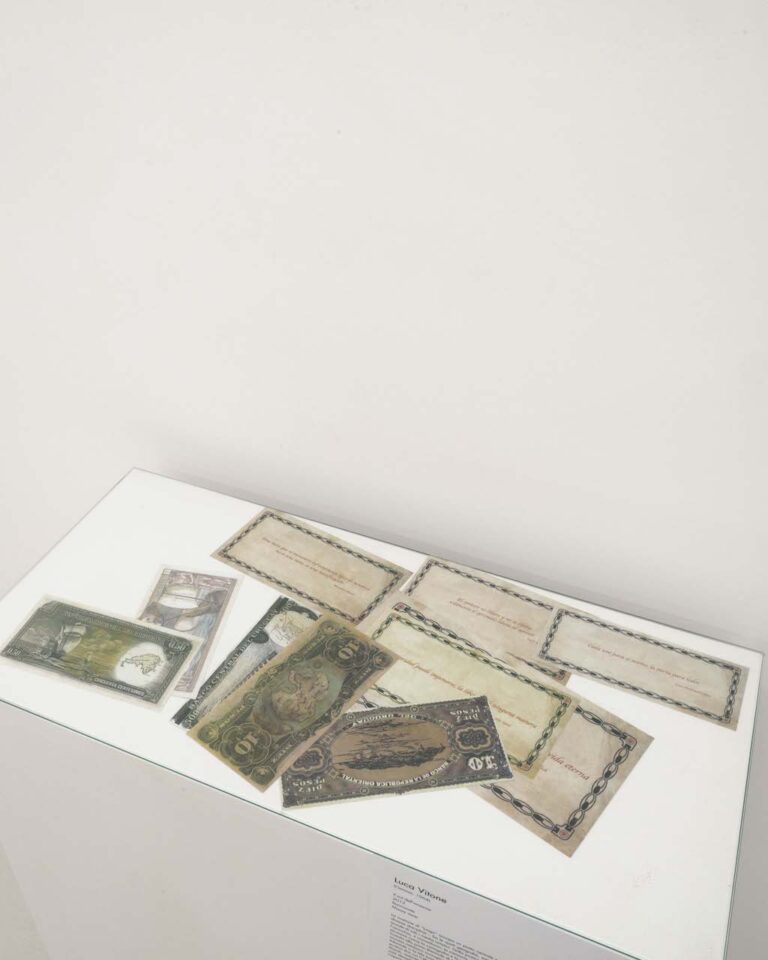

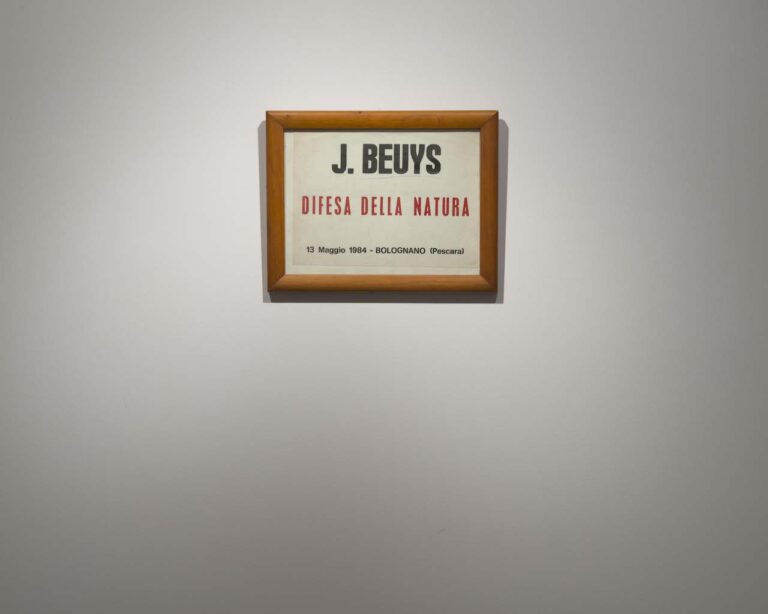

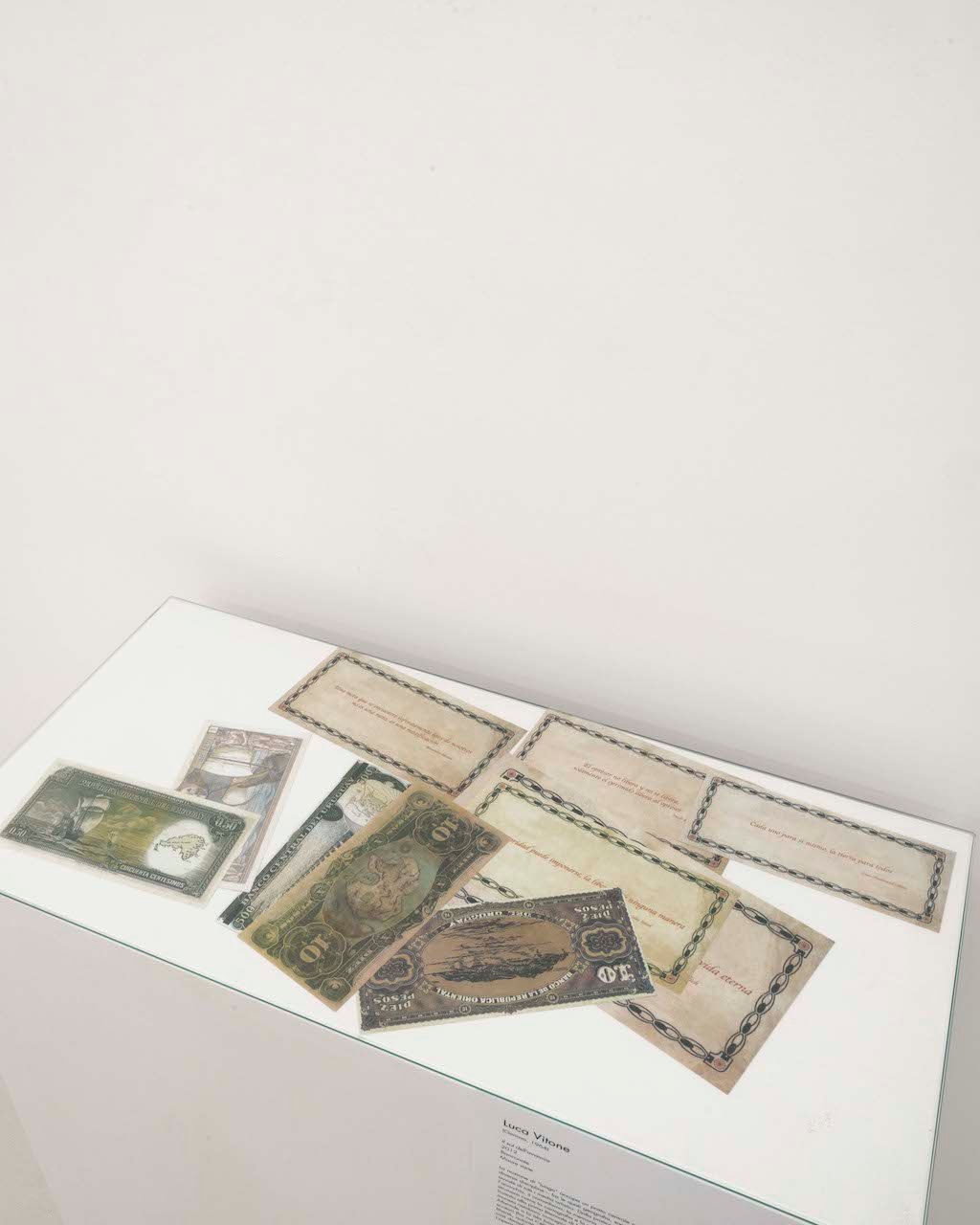

Their collection of modern and contemporary art is characterized by a certain freedom in terms of chronology, media, themes and artists. However, there are some pillars linked, for example, to movements such as visual poetry or areas such as feminist, as well as to specific artists (such as Mirella Bentivoglio, Joseph Beuys, Matteo Fato, Luca Vitone). How was interest in these collections determined?

In the first case, feminism, and within it the friendship with Mirella Bentivoglio and the purchase of everything possible from her activity, is associated with special admiration and thoughts of revolt (for Mirella Bentivoglio, institutional, expensive, museum distortions testify to the incurable distortion). Patriarchy and a male civilization). So it was about female alphabets and primers, household materials, a certain aversion to the market and valuations, to the size of the work, to personal spaces, installations, monographic catalogs, price lists and the exhibitionism of the paintings.

But in the interest of such radical forms of poetic guerrilla warfare, as with all visual poetry, lies the memory of our personal family history and of Italy: parents who emigrated to the north, workers at Fiat, the horror of the factory, advertising indoctrination and its inescapable Fate as happy consumers who sit in front of the television every evening. Visual poetry is a constant rage against the languages of power and persuasion.

How collecting is linked to your intellectual dimension – in Giannis’ case, music philology and theater translation; in Giuseppe’s musicology and art history?

With the end of adolescence, writing has already replaced the oral word and conversations, late-night dialogues, the intellectual exercise of youthful friendship. The work of art then even becomes a monologue. Collecting is a concern for what one has and a cancellation of the youthful break with tradition. But collecting is only superficially connected to the intellectual dimension, only to give the collection a tone, a dignity, a justification; The more the years pass, the more we realize that we collect to order and set up altars, mausoleums, triumphal arches, crowns, showpieces, boasts and vanities, that is, that collecting allegorically belongs to a vulgar source that consists in seizing Plundering, in plundering, in hoarding, in having more (the themes plundered with fever are time, days, lives, and one takes from one’s entire past, and if anything the intellectual dimension serves to be more zealous): the final Horizon is to stand up a little absurd, amid perplexed and astonished friends and family, as princes, pharaohs and rulers of no one knows which kingdom (often the end result to the mundane eye is an incomprehensible, preserved and piled pile of rubble).

On the occasion of the exhibition in Pescara, a selection of different materials from your collection will be presented, revolving around an idea of art as poetic struggle, need for freedom, disobedience, social intervention and participation. How did these issues come to attention and how did your collecting strategy respond to this?

This specific type of research initially arose from a social discomfort, that is, from an embarrassment towards art galleries, with the contempt that arises for wealthy environments and with a certain economic arrogance, and where the distinction is based on class and value, and therefore inevitable a political disgrace. Almost all the most radical searches for a poetic struggle have this clear distinguishing feature: they are gratuitous, that is, they bring about, first of all, a reversal of economics up to and including the cult of the gift. These works are the most difficult to find because they were provided for free and scattered, they found the market inattentive, not complicit, they could be lost and scattered: poor, unrecognizable (most often simply because they were). They had no frame or poor materials were chosen, that is, even outside the comfort of the studio), they are works subject to loss because they work among people and on the street, outside the reassuring walls of a museum or gallery forgo the prestige of market value, become part of the legend and require attention and care from the collector. Their original status is already a political act, a dream of social community: they were something that cost nothing (they adhere to the first rule of paradisiacal economics: “Get it for free”).

Simone Ciglia